Redesigning Education Beyond Procedure in the Age of AI

Redesigning Education Beyond Procedure in the Age of AI

Published

Modified

AI excels on known paths, so schools must shift beyond procedure Assessments should reward framing and defense under uncertainty This prepares students for judgment in an AI-driven world

Every era has its pivotal moment. Ours came when an AI system scored a gold medal at the world's toughest student math contest. It solved five out of six problems in the International Mathematical Olympiad within four-and-a-half hours, providing clear solutions that official coordinators graded for a total of 35 points. This accomplishment highlights not only the power of computation but also a key shift in our educational systems. When the route to a solution is clear—when methods are established, tactics are defined, and proofs can be systematically searched—machines aren't just helpful; they outperform humans. They work tirelessly within established techniques. If education continues to prioritize mastering these techniques as the highest achievement, we risk judging students on how well they imitate a machine. The correct response is not to reject the machine but to change the focus of the contest. We should teach for the unknown path by encouraging problem finding, framing models, auditing assumptions, transferring knowledge across domains, and crafting arguments under uncertainty. This shift is not only practical, but it is also urgently needed.

The Known Path Is Now a Conveyor Belt

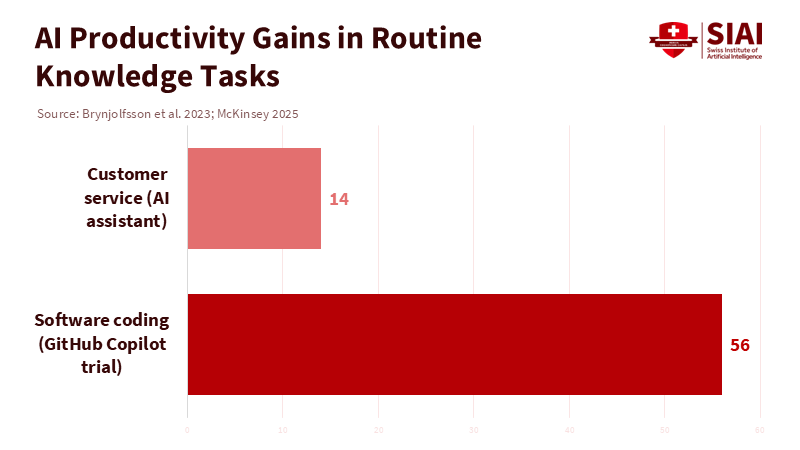

Across various fields, evidence is coming together. When a task's route is clear and documented, AI systems speed up processes and reduce variability. In controlled experiments, developers using an AI pair programmer completed standard coding tasks about 56 percent faster. This result has been replicated in further studies. Customer service agents using a conversational assistant were 14 percent more productive, with greater gains for novices—significant for education systems that want to help lower performers. These findings reflect what happens when patterns are recognizable and "next steps" can be predicted from a rich history of similar tasks. In mathematics, neuro-symbolic systems have reached a significant milestone. AlphaGeometry solved 25 of 30 Olympiad-level geometry problems within standard time limits, nearing the performance of a human gold medalist, and newer systems have formalized proofs more extensively. This is what we should expect when problem areas can be navigated through guided searches of known tactics, supported by larger datasets of worked examples and verified arguments.

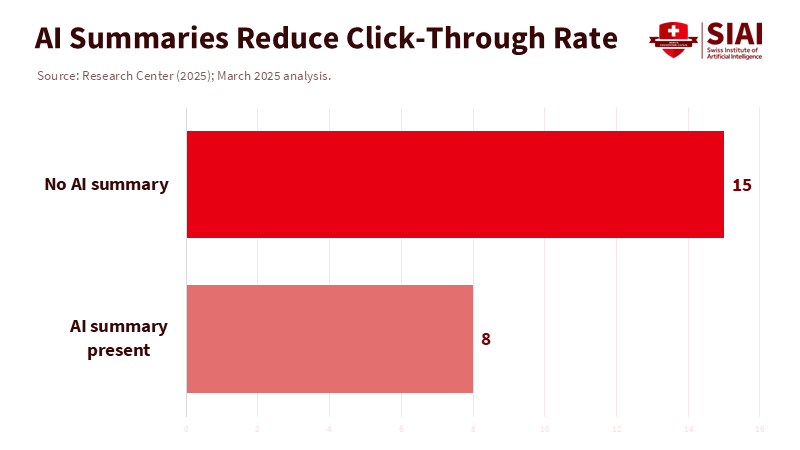

The policy issue is straightforward: if education continues to allocate most time and grades to known-path performance—even in prestigious courses—students will understandably look for tools to accelerate their success along these paths. Recent international assessments highlight the consequences of poorly structured digital time. In PISA 2022, students spending up to one hour per day on digital devices for leisure scored 49 points higher in mathematics than those using them for five to seven hours; pushing leisure screen time beyond one hour, and performance declines sharply. The takeaway is not to ban devices but to stop making schoolwork a device-driven search for known steps. The broader labor market context supports this point. Mid-range estimates suggest that by 2030, about a third of current work hours could be automated or accelerated, impacting routine knowledge tasks—exactly the procedural skills that many assessments still prioritize. Education systems that focus on the conveyor belt will inadvertently grade AI usage instead of human understanding.

Method note: To clarify ideas, consider a 15-week algebra course with four hours of homework each week. If 60 percent of graded work is procedural and AI tools cut completion time for those tasks by a conservative 40 percent, students save about 1 hour per week, 15 hours per term. The question is what to do with those hours: focus on more procedures or the skills machines still struggle to automate—defining a problem, managing uncertainty, building a model worth solving, and justifying an answer to an audience that challenges it.

Designing for Unknown Paths

What does it mean to teach for the unknown path while maintaining fluency? The initial step is curricular: treat procedures as basic requirements and dedicate class time to deeper concepts. This means shifting from "Can you find the derivative?" to "Which function class models this situation appropriately for the decision at hand, and what error margin ensures robustness?" From "Solve for x" to "Is x even the right variable to consider?" From "Show that the claim is valid" to "If the claim is false, how would we know as early and cheaply as possible?" The aim is not to confuse students with endless questions for the sake of it, but to structure exercises around selecting, defining, and defending approaches under uncertainty—skills that remain distinctly human, even as computations become quicker.

There are practical ways to achieve this. Give students the answer and ask them to create the question—an exercise that demands attention to assumptions and limitations. Require an "assumption log" and a one-page "model card" with any multi-step solution. This document should outline what was constant, what data were acceptable, what alternatives were explored, and the principal risks of error. Use AI as a baseline: let students develop a solid procedural solution, then evaluate their responses—by challenging, generalizing, or explaining when it might lead them astray. Anchor practice in real inquiries ("What influenced attendance last quarter?") rather than just symbolic manipulation. When students need to make approximations, they should justify the approach they selected and show how their conclusions change as the estimation criteria relax. These are not optional extras; they are habits we can teach and assess.

Research shows that well-designed digital tools can enhance learning when they focus on practice and feedback instead of replacing critical thinking. A significant evaluation linked to Khan Academy found positive learning outcomes when teachers dedicated class time to systematic practice on core skills, while quasi-experimental studies reported improvements at scale. Early tests of AI tutors show higher engagement and faster mastery compared to lecture-based controls, particularly among students who start behind—again, a significant equity issue. The key point is not that an AI tutor teaches judgment. Instead, it's that thorough, data-informed practice frees up teacher time and student energy for developing judgment if— and only if—courses are designed to climb that ladder.

What Changes on Monday Morning

The most crucial factor is assessment. Institutions should immediately transform some summative tasks into "open-tool, closed-path" formats. Students may use approved AI systems for procedural tasks, but they will be scored on the decisions made before those steps and the critiques that follow. Provide the machine's answer and assess the student's follow-up: where it strayed, what different model might change the outcome, which signals mattered most, and which assumption, if incorrect, would compromise the result. Require verbal defenses with non-leading questions—five minutes per student in small groups or randomized presentations in larger classes—to ensure that written work reflects accurate understanding, since leisure device time correlates with significant performance drops. Schedule "deep work" sessions where phones are set aside and tools chosen intentionally, not reflexively.

For administrators, the budgeting focus should be on teacher time. If AI speeds up routine feedback and grading, those hours should be reclaimed for engaging, studio-style seminars where students present and defend their modeling choices. Pilot programs could establish a set target—such as two hours of teacher contact time per week shifted from grading procedures to facilitating discussions—and then monitor the results. Early signs in the workplace suggest that these gains are real. Surveys indicate that AI tools are quickly being adopted across functions, and studies show that saved time often gets redirected into new tasks instead of being wasted. However, redeployment is not automatic. Institutions should integrate this into their schedules: smaller discussion groups, rotating "devil's advocate" roles, and embedded writing support focused on evidence and reasoning rather than just grammar.

Policymakers have the most to address regarding incentives. Accountability systems need to stop awarding most points for de-contextualized procedures and instead assess students' abilities to diagnose, design, and defend. One option is to introduce moderated "reasoning audits" in high-stakes exams: a brief, scenario-based segment that provides a complex situation and asks candidates to create a justified plan instead of completing a finished calculation. Another approach is to fund statewide assessment banks of open-context prompts with scoring guidelines that reward managing uncertainty—explicitly identifying good practices such as bounding, triangulating data sources, and articulating a workable model. Procurement can also help: require that any licensed AI system records process data (queries, revisions, model versions) to support clear academic conduct policies rather than rigid bans. Meanwhile, invest in teacher professional learning focused on a few solid routines: defining a problem, conducting structured estimations, drafting a sensitivity analysis, and defending assumptions with a brief presentation. These skills are transferable across subjects; they are essential for mastering the unknown path.

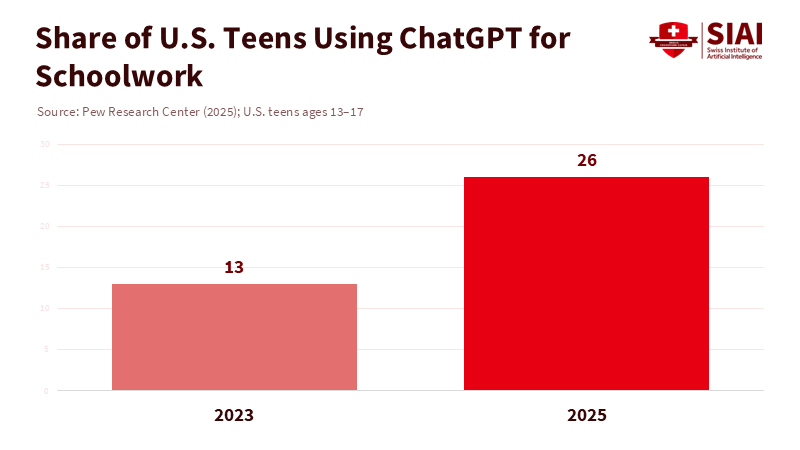

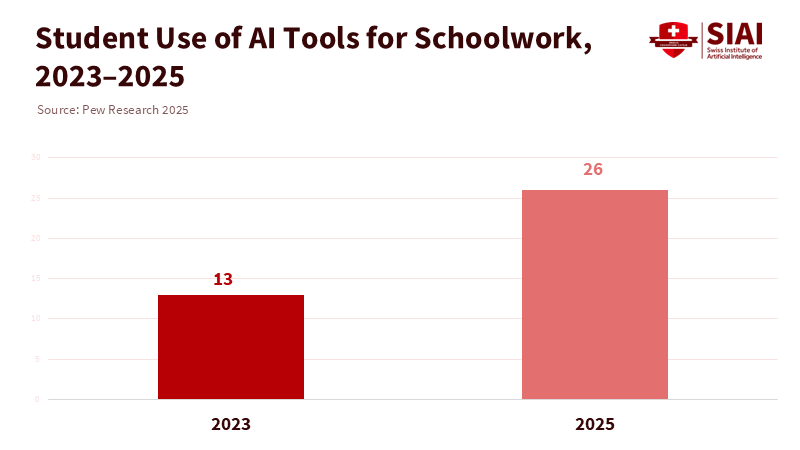

Finally, we should be honest about student behavior. The use of AI for schoolwork among U.S. teens increased from 13 percent to 26 percent between 2023 and 2025, with this trend crossing demographic boundaries. Universities report similar patterns, with most students viewing AI as a study aid for explanation and practice. Ignoring these tools only drives their use underground and misses a chance to teach how to use them wisely. A simple institutional policy can align incentives: allow the use of AI for known steps if documented, and ensure that grades are mainly based on what students do that the model cannot define—tasks, justifying approaches, challenging outputs, and communicating effectively with a questioning audience.

We anticipate familiar critiques. First, won't shifting focus away from procedures weaken fluency? Evidence from tutoring and structured practice suggests otherwise—students improve more when routine practice is disciplined, clear, and linked to feedback, especially if time is shifted toward transfer. Second, won't assessing open-ended tasks be too subjective? Not if rubrics clearly define the criteria for earning points—stating assumptions, bounding quantities, testing sensitivity, and anticipating counterarguments. Third, isn't relying on AI risky because models can make mistakes? That's precisely the goal of teaching the unknown path. We include the model where it belongs and train students to identify and recover from its errors. Fourth, doesn't this favor students who are already privileged? In fact, the opposite can hold. Research shows that the most significant productivity gains from AI assistance tend to benefit less-experienced users. If we create tasks that value framing and explanation, we maximize class time where these students can achieve the most significant growth.

We also need to focus on attention. The PISA digital-use gradient serves as a reminder that time on screens isn't the issue; intent matters. Schools should adopt a policy of openly declaring tool usage. Before any assessments or practice sessions, students should identify which tools they plan to use and for which steps. Afterwards, they should reflect on how the tool helped or misled them. This approach safeguards attention by turning tool selection into a deliberate choice rather than a habit. It also creates valuable metacognitive insights that teachers can guide. Together with planned, phone-free sessions and shorter, more intense tasks, this is how we can make classrooms places for deep thinking, not just searching.

The broader strategic view is not anti-technology; it advocates for judgment. Open-source theorem provers and advanced reasoning models are improving rapidly, resetting the bar for procedural performance. State-of-the-art systems are achieving leading results across competitive coding and multi-modal reasoning tasks. If we keep treating known-path performance as the pinnacle of educational success, we will find that standards are slipping right from under us.

We started with a gold-medal proof counted in points. Now, let's look at a different measure: the minutes spent on judgment each week, for each student. A system that uses most of its time on tasks a machine does better will drain attention, lead to compliance games, and widen the gap between credentials on paper and actual readiness. A system that shifts those minutes to framing and defense will produce a different graduate. This graduate can select the right problem to tackle, gather the tools to address it, and handle an informed cross-examination. The way forward isn't about trying to outsmart the machine; instead, it's about creating pathways where none exist and teaching students to build them. This is our call to action. Rewrite rubrics to emphasize transfer and explanation. Free up teacher time for argument. Require assumption logs and sensitivity analyses. Make tool use clear and intentional. If we do this, the next time a model achieves a perfect score, we will celebrate and then pose the human questions that only our students can answer.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2023). Generative AI at work (NBER Working Paper No. 31161). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Castelvecchi, D. (2025). DeepMind and OpenAI models solve maths problems at level of top students. Nature News.

DeepMind. (2025, July 21). Advanced version of Gemini with Deep Think officially achieves gold-medal standard at the International Mathematical Olympiad.

Education Next. (2024, December 3). AI tutors: Hype or hope for education?

Khan Academy. (2024, May 29). University of Toronto randomized controlled trial demonstrates a positive effect of Khan Academy on student learning.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2023, June 14). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier.

McKinsey. (2025, January 28). Superagency in the workplace: Empowering people to unlock AI's full potential at work.

OECD. (2023, December). PISA 2022: Insights and interpretations.

OECD. (2024, May). Students, digital devices and success: Results from PISA 2022.

OpenAI. (2025, April 16). Introducing o3 and o4-mini.

Peng, S., Kalliamvakou, E., Cihon, P., & Demirer, M. (2023). The impact of GitHub Copilot on developer productivity (arXiv:2302.06590).

Pew Research Center. (2025, January 15). About a quarter of U.S. teens have used ChatGPT for schoolwork, double the share in 2023.

Trinh, T. H. et al. (2024). Solving Olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature, 627, 768–774.

The Guardian. (2025, September 14). How to use ChatGPT at university without cheating: "Now it's more like a study partner."