The LLM Pricing War Is Hurting Education—and Startups

The LLM Pricing War Is Hurting Education—and Startups

Published

Modified

Cheaper tokens made bigger bills The LLM pricing war squeezes startups and campuses Buy outcomes, route to small models, and cap reasoning

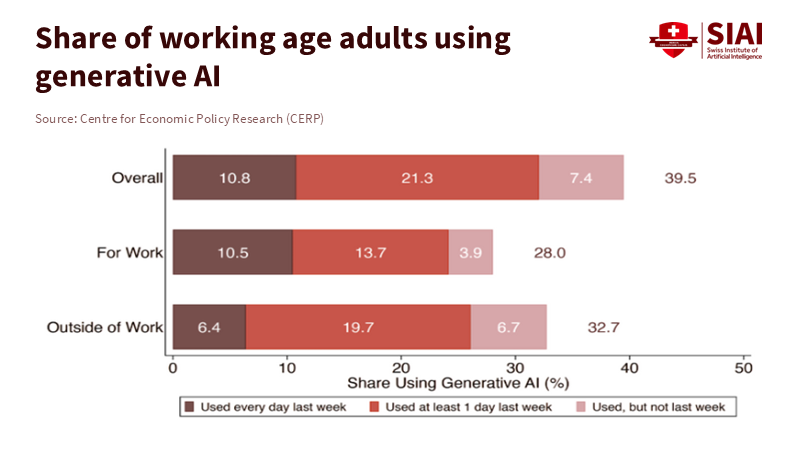

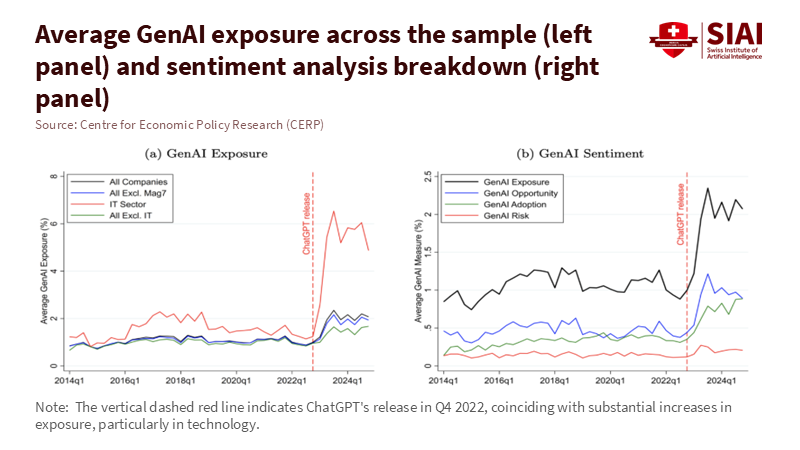

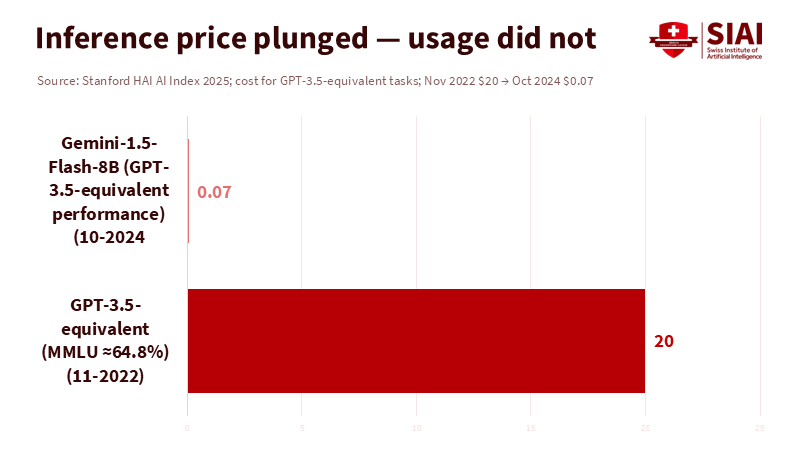

A single number illustrates the challenge we face: $0.07. This is the lowest cost per million tokens that some lightweight models achieved in late 2024, down from about $20 just 18 months earlier. Prices dropped significantly. However, technology leaders are reporting rising cloud bills that spike unexpectedly. University pilots that initially seemed inexpensive now feel endless. The paradox is straightforward. The LLM pricing war made tokens cheaper, but it also made it easy to use many more tokens, especially with reasoning-style models that think before they answer. Costs fell per unit but increased in total. Education buyers and AI startups are caught on the wrong side: variable usage, limited pricing power, and worried boards keeping an eye on budgets. Unless we change how we purchase and utilize AI, lower token prices will continue to result in higher bills.

We need to rethink the problem. The question is not “What is the lowest price per million tokens?” It is “How many tokens will the workflow use, who controls that number, and what happens when the model decides to think longer?” The LLM pricing war has shifted competition from price tags to hidden consumption. That is why techniques like prompt caching and model routing are now more critical than the initial price of a flagship model.

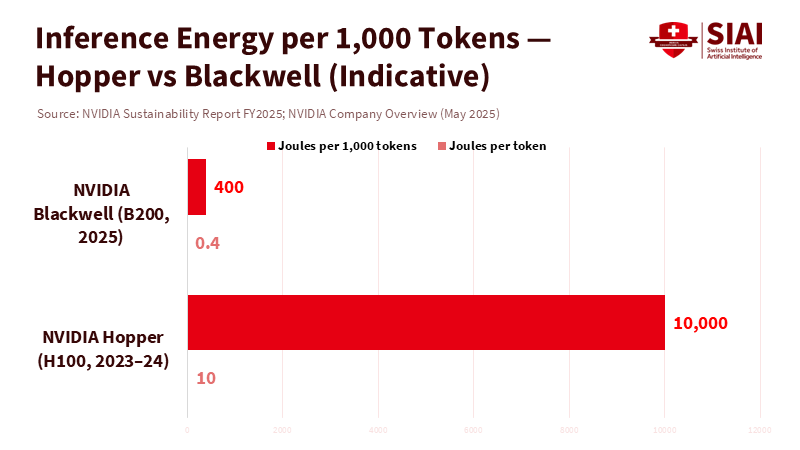

There’s another twist. Significant price cuts often conceal a shift in model behavior. New reasoning models add internal steps and reasoning tokens, with developer-set effort levels that can increase costs for identical prompts. Per-token fees may seem stable, but the total number of tokens does not. The billing line grows with every additional step.

The LLM pricing war: cheaper tokens, bigger bills

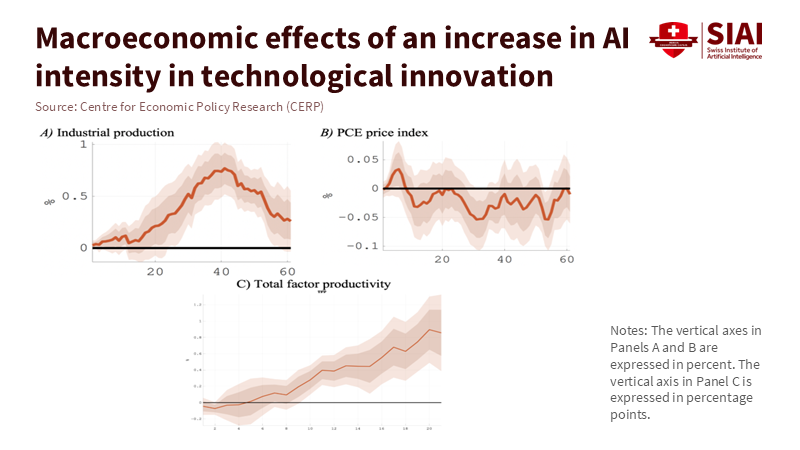

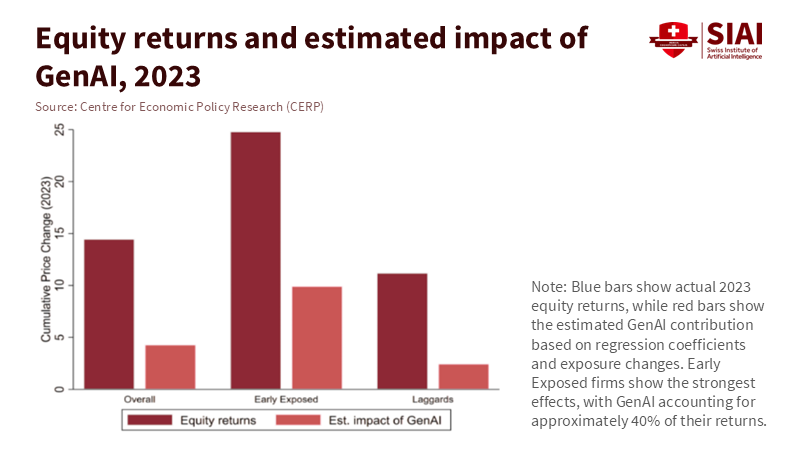

First, let’s look at the numbers. The Stanford AI Index reports a significant drop in inference prices for smaller, more efficient models, with prices as low as cents per million tokens by late 2024. However, campus and enterprise costs are trending in the opposite direction: surveys show a sharp increase in cloud spending as generative AI moves into production, with many IT leaders struggling to manage and control these costs. Both situations are actual. Prices fell, but bills grew. The cause is volume. As models become faster and cheaper, we give them more work. When we add reasoning, they generate many more tokens for each task. The curve rises again.

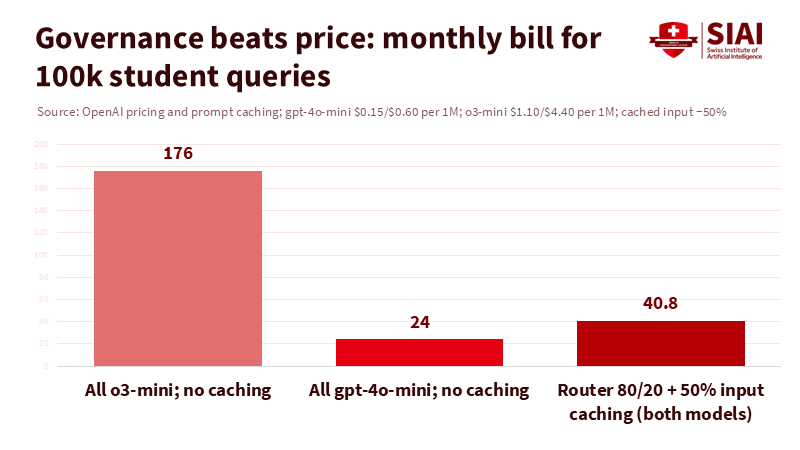

The mechanics turn this curve into a budget issue. Prompt caching can reduce input token costs by half when prompts are repeated, provided the cache hits, and only for the cached span. Reasoning models offer effort controls—low, medium, high—that change the hidden thought processes and, therefore, the bill. Providers now offer routers that select a more cost-effective model for simple tasks and a more robust one for more complex tasks. This represents progress, but it also serves as a reminder: governance is crucial. Without strong safeguards, the LLM pricing war leads to increased usage at the expense of efficiency and effectiveness. Cost figures mentioned are sourced from public pricing pages and documents; unit prices vary by region and date, so we use the posted figures as reference points.

How the LLM pricing war squeezes startups and campuses

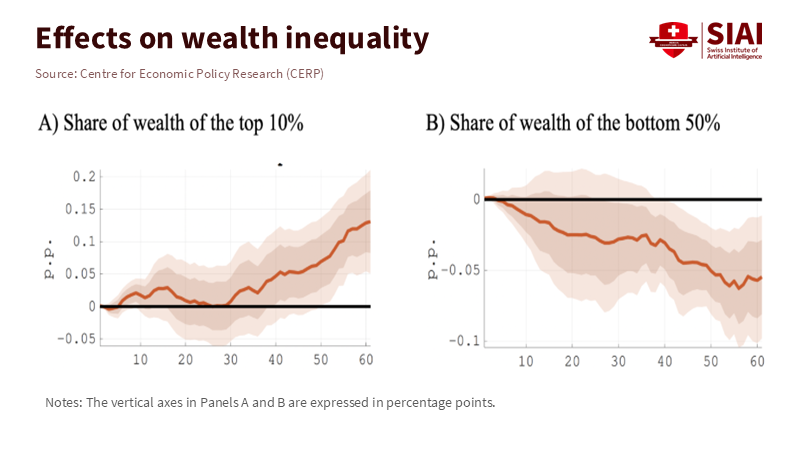

Startups face the harshest math. Flat-rate consumer plans disappeared once users automated agents to operate continuously. Venture-backed firms that priced at cost to grow encountered runaway token burn as reasoning became popular. This resulted in consolidation. The inflection point shifted after its leaders and a significant portion of its team joined Microsoft. Adept’s founders and team moved to Amazon. These are not failures of science; they are failures of unit economics in a market where established companies can subsidize and manage workloads at scale. The LLM pricing war turns into a funding war the moment usage spikes.

Education buyers experience a similar squeeze. Many pilots initially experience limited and uneven financial impacts, while cloud costs remain unpredictable. Some industry surveys tout strong ROI, while others, including reports linked to MIT, find that most early deployments demonstrate little to no measurable benefit. Both can be accurate. Individual function-level successes exist, but overall value requires redesigning work, not just switching tools. For universities, this means aligning use cases with metrics such as “cost per graded assignment” or “cost per advising hour saved,” rather than just cost per token. We analyze various surveys and treat marketing-sponsored studies as directional while relying on neutral sources for trend confirmation.

The competitive landscape is shifting. Leaderboards now show open and regional players trading positions rapidly as Chinese and U.S. labs cut prices and release new products. Champions change from quarter to quarter. Even well-funded European players must secure large funding rounds to stay competitive. The LLM pricing war involves more than just price; it encompasses computing access, distribution, and time-to-market. For a university CIO, this constant change means procurement must assume switching—both technically and contractually—from the beginning.

Escaping the LLM pricing war: a policy playbook for education

The way out is governance, not heroics—first, purchase outcomes, not tokens. Contracts should link spending to specific services—such as graded documents, redlined pages, or resolved tickets—rather than raw usage. A writing assistant that charges per edited page aligns incentives; a metered chat endpoint does not. Second, demand transparency in routing. Suppose a vendor automatically switches to a more cost-effective model. In that case, that’s acceptable, but the contract must detail the baseline model, audit logs, and limits for reasoning effort. This turns “smart” routing into a controllable dial rather than a black box. Third, make cache efficiency a key performance indicator. If the average cache hit rate falls below an agreed threshold, renegotiate or switch providers. These steps transform the LLM pricing war from a hidden consumption issue into a manageable service.

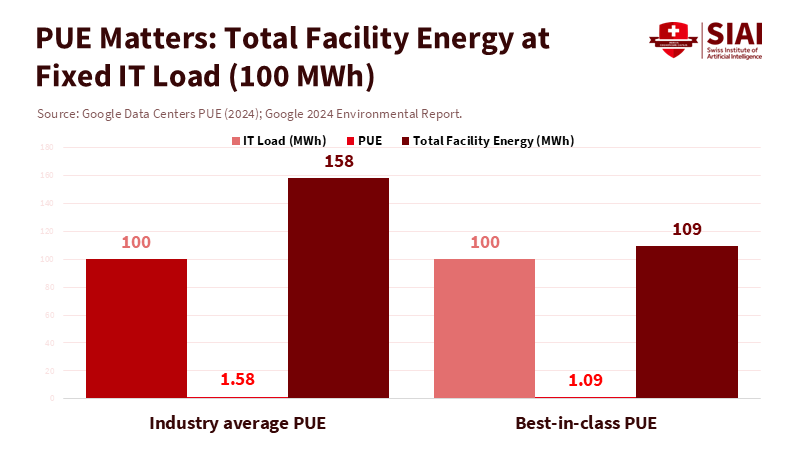

Now for the implementation side. Universities should stick to small models and only upgrade when tests prove the need for it. For tutoring, classification, rubric-based grading, and basic drafting, the standard should be compact models, with strict budgets for more complex reasoning. A router that you control should enforce this standard. Cloud vendors now offer native prompt-routing that balances cost and quality; adopt it, but require model lists, thresholds, and logs. Pair this with a simple abstraction layer, allowing you to switch providers without rewriting all your applications. Recommendations for routing align with vendor documents and general financial operations principles; specific parameters depend on your technology stack.

A narrow path to durable value

This situation is also a talent issue. Schools need a small FinOps-for-AI team that can enforce cost policies and stop unsafe routing. This team should operate between academic units and vendors, publish monthly cost/benefit reports, and manage cache and router metrics. Simple changes can help: lock prompt templates, condense context, favor retrieval over long histories, and establish strict limits on the number of tokens per session. These measures may seem mundane, but they save real money. They also make value measurable in ways that boards can trust.

On the vendor side, we should stop rewarding unsustainable pricing. If a startup’s quote seems “too good,” assume someone else is covering the costs. Inquire about how long the subsidy lasts, how the routing operates under load, and what happens when a leading model becomes obsolete. Include “time-to-switch” in the RFP and score it. Require escrowed red-team prompts and regression tests to ensure switching is possible without sacrificing safety or quality. For research labs, funders should allocate budget lines for test-time computing and caching, so teams do not conceal usage in student hours or through shadow IT.

There is reason for optimism. Some model families provide excellent value at a low cost per token, and the market is improving at directing simple prompts to smaller models. OpenAI, Anthropic, and others offer “effort” controls; when campuses set them to “low” by default, they reduce waste without compromising learning outcomes. The message is clear: the most significant savings do not come from waiting for the next price cut; they come from saying “no” to unbounded reasoning for routine tasks.

The final change is cultural. Faculty need guidance on when not to use AI. A course that grades with rubrics and short answers can function well with small models and concise prompts. An advanced coding lab may only require a heavier model for a few steps. A registrar’s chatbot needs to rely on cached flows before escalating to human staff. The goal is not to hinder innovation. It is to treat reasoning time like lab time—scheduled, capped, and justified by outcomes.

Returning to that initial number—$0.07 per million tokens—reveals the illusion it created. The LLM pricing war provided a headline that every CFO wanted to see. But the details reveal usage, and usage is elastic. If we continue to buy tokens instead of outcomes, budgets will continue to break as models think longer by design. Education leaders should adopt a new approach: prioritize cost control by default, manage reasoning effectively, cache resources, and contract for results. Startups should price transparently, resist flat-rate traps, and focus on service quality rather than subsidies. Following this strategy will help eliminate the paradox. Cheap tokens can transform from a trap into the foundation for affordable, equitable, and sustainable AI in our classrooms and labs.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Anthropic. (2024). Introducing Claude 3.5 Sonnet. Pricing noted at $3/M input and $15/M output tokens.

Artificial Analysis. (2025). LLM Leaderboard—Model rankings and price/performance.

AWS. (2025). Understanding intelligent prompt routing in Amazon Bedrock.

Axios. (2025). OpenAI releases o3-mini reasoning model.

Ikangai. (2025). The LLM Cost Paradox: How “Cheaper” AI Models Are Breaking Budgets.

Medium (Downes, J.). (2025). AI Is Getting Cheaper.

McKinsey & Company. (2025). Gen AI’s ROI (Week in Charts).

Microsoft Azure. (2024). Prompt caching—reduce cost and latency.

Microsoft Azure. (2025). Reasoning models—effort and reasoning tokens.

Mistral AI. (2025). Raises €1.7B Series C (post-money €11.7B).

Okoone. (2025). Why AI is making IT budgets harder to control.

OpenAI. (2024). API Prompt Caching—pricing overview.

OpenAI. (2025). API Pricing (fine-tuning and cached input rates).

OpenRouter. (2025). Provider routing—intelligent multi-provider request routing.

Stanford HAI. (2025). AI Index 2025, Chapter 1—Inference cost declines to ~$0.07/M tokens for some models.

Tangoe (press). (2024). GenAI drives cloud expenses 30% higher; 72% say spending is unmanageable.

TechCrunch. (2025). OpenAI launches o3-mini; reasoning effort controls.

TechRadar. (2025). 94% of ITDMs struggle with cloud costs; AI adds pressure.

The Verge. (2025). OpenAI’s upgraded o3/o4-mini can reason with images.

Tom’s Hardware. (2025). MIT study: 95% of enterprise gen-AI implementations show no P&L impact.