After the Google Ruling, Antitrust Became a Blunt Instrument for AI Competition

After the Google Ruling, Antitrust Became a Blunt Instrument for AI Competition

Published

Modified

Antitrust breakups miss the real battleground: AI assistants, not blue links Prioritize interoperability and open defaults to keep markets contestable Track assistant-led discovery, not just search share, to safeguard users and educators

While the government's major search case crawled from filing to remedy over nearly five years, AI assistants shifted from curiosity to a daily habit. ChatGPT alone now handles about 2.5 billion prompts each day and logs billions of visits each month. This change in user behavior—where people ask systems to summarize answers rather than provide links—matters more for competition's future than whether a judge forces a company to sell a browser or a mobile operating system. The court's decision not to mandate a breakup fell flat in policy circles, even though Google retained its dominance. By the time the gavel fell, competition had already evolved. Search is becoming a feature of assistants, not the reverse. However, the legal tools remain focused on past battles. If we continue to attack shrinking link lists while assistants capture user demand, we will miss the market and the public interest it serves.

The market shifted while the law took its time

The court did not require Google to sell Chrome or Android. This decision spared the economy from the shock of a significant split. It highlighted a deeper issue: traditional antitrust solutions are too slow and too limited for markets that change rapidly in response to model updates and user habits, which can shift in just weeks. The legal timeline included a 2020 complaint, a 2024 opinion on liability, a spring 2025 trial for remedies, and a September 2025 order that fell short of a breakup, even as it tightened conduct rules. Meanwhile, OpenAI released a web-connected search mode to the public, Microsoft integrated Copilot into Windows and Office, and newcomers like Perplexity turned retrieval-augmented answers into a daily routine. The contest now looks different. It's about who sits between users and the web—who summarizes, cites, and takes action. A solution created for default search boxes cannot, on its own, manage this new critical point.

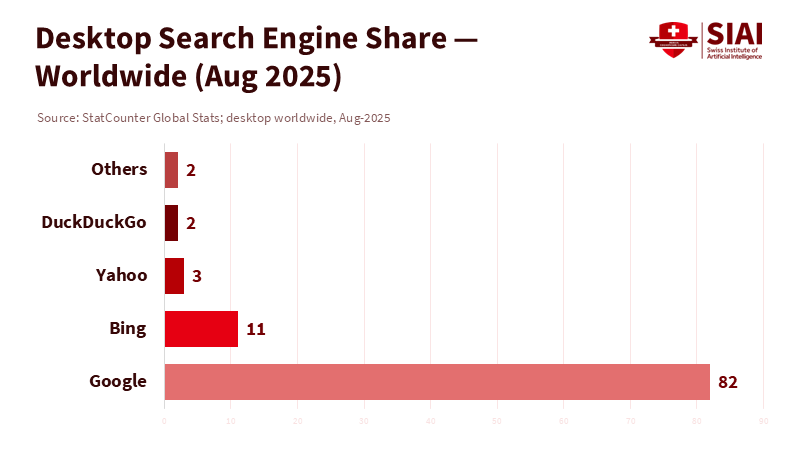

The numbers tell two stories. On one hand, Google's global search share remains vast, about 90% across devices, with Bing below 4%, suggesting a strong push for a structural fix. On the other hand, the part of the market most relevant to office work and professional research shows Bing creeping up toward double digits worldwide, and AI assistants are taking on queries that used to be traditional searches. A more credible perspective is that the incumbent is not collapsing, but rather, the space for competition has shifted. StatCounter measures shares based on page-view data and tends to underestimate usage within assistant interfaces, while Similarweb's "visits" indicate traffic, not unique visitors. In simple terms, if assistants provide answers before links load, their growth will not immediately be reflected in search-engine shares, even as they capture user intent. Policies that wait for share metrics to change may arrive two product cycles too late.

Measuring the real competition: assistants vs. links

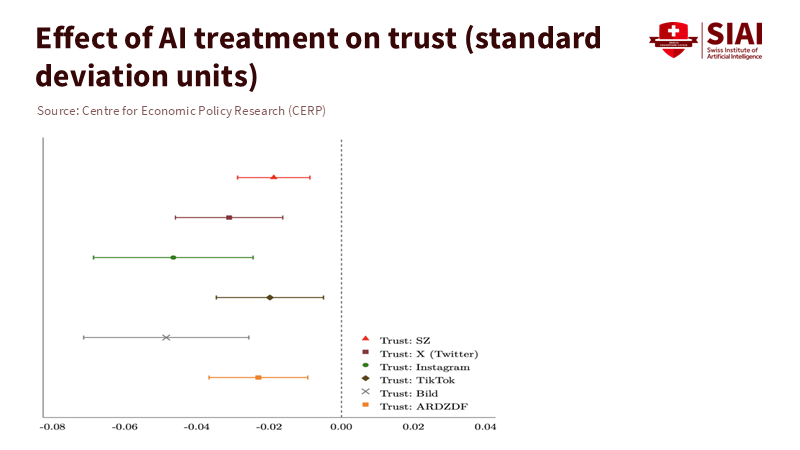

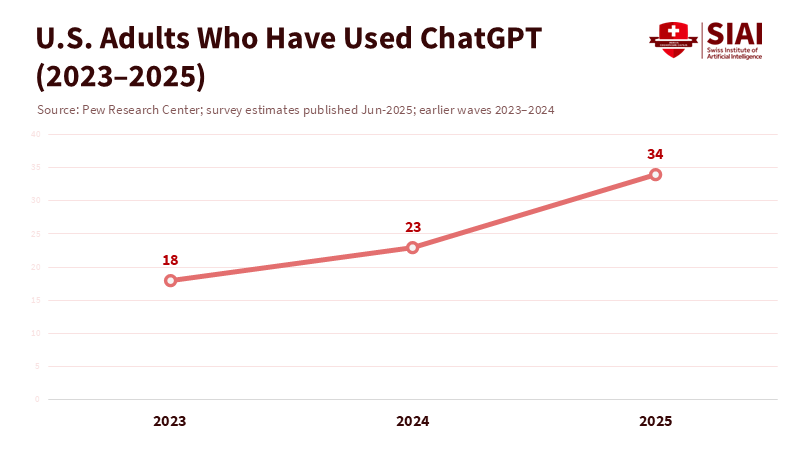

A better measure is emerging. Pew reports that the share of U.S. adults using ChatGPT has roughly doubled since 2023, and the Reuters Institute notes that chatbots are now recognized as a source of news discovery for the first time. Additionally, OpenAI's own usage research and impartial traffic data indicate that information-seeking is a core use of these assistants, not just a side feature. We count assistant-assisted discovery as part of the search market. In that case, Google's field of competitors now includes OpenAI/ChatGPT, Microsoft's Copilot, Perplexity, and specialized assistants, each vying for the first interaction with a question and the final interaction before an action is taken. This changes the discussion around remedies. Default settings on browsers and phones still matter, but control over model inputs, training data, and real-time content licensing determines the speed and quality of responses. Those who secure scalable rights to news, maps, product catalogs, academic abstracts, and local listings—not just access to a search bar—will dictate the pace of competition.

In this context, the September decision appears less as the end of competition policy and more as a reflection on the kind of competition policy we've tried to apply. The court's ruling against a breakup, combined with stricter conduct rules, will not halt the shift from queries to prompts. It does little to lower the significant barriers in artificial markets, such as computing costs, access to advanced models, and the cost of acquiring legal data. Regulators outside the U.S. have begun to change their strategies. The EU's Digital Markets Act has mandated choice screens and some unbundling, with early indications of modest gains for browsers. At the same time, the U.K.'s new DMCC framework empowers the CMA to set specific conduct rules for firms with "strategic market status." These tools are proactive and sector-specific. They move faster and can be modified to address assistant-related issues. The U.S. does not need a mirror image of these strategies, but rather a plan that recognizes assistance as a key component of the competitive landscape—not just search boxes.

From punishment to interoperability: a new plan

If "antitrust is dead," it is only because adapting structural fixes rarely changes behavior quickly enough. The alternative is not deregulation; it is making interoperability a policy priority. Begin with data. Courts can compel disclosures in specific areas, but policymakers should establish licensed data-sharing platforms for categories essentially treated as public goods: geography, civic information, public safety, and basic product information. Pair mandatory licensing at fair, transparent rates with open technical "ports"—stable APIs, standardized formats, and audit logs—so any qualified assistant can connect. This would reduce the importance of exclusive vertical integrations and shift the advantage to the interface, not the inputs. The CMA's work on foundational models is a valuable example, citing access to computing and data as major hurdles and proposing principles for fair access. Turning those principles into law and procurement measures would give challengers a chance that doesn't rely on rare and lengthy breakups.

Next, address defaults where they still impact users, but measure success based on switching costs, not just "choice screens." The EU has demonstrated that choice screens can help, yet design and implementation are crucial; earlier versions were awkward and had inconsistent effects. Make defaults portable: a user's chosen assistant should be accessible across devices and applications unless they opt out. Require one-tap rerouting for any query field to the user's current default assistant, and prohibit contract terms that penalize manufacturers for offering rival options upfront. Importantly, audit the interactions when AI summaries appear above links. If Google's summaries lead to fewer downstream clicks, require the disclosure of metrics, and offer parity options for rival answer modules, while ensuring clear source labeling. The goal is not to hinder Google's progress but to prevent a single gatekeeper from dominating the interface when assistants are designed to be interchangeable.

At the same time, we need to stop acting as if ad tech and discovery are separate entities. The ongoing phase of ad-tech remedies will affect who can finance free assistants on a large scale. A transparent, auditable auction with open interfaces enables competitors to purchase distribution without relying on an incumbent's opaque systems. If, as the DOJ contends, parts of Google's ad structure have been unlawful monopolies, the solution must include not only structural options but also opening auction rules and ensuring third-party assistants have fair access commitments that facilitate commercial traffic. The markets for attention fuel the engines; cutting off the toll booth reduces the incumbents' ability to subsidize exclusive defaults. This approach is more likely to promote competition than splitting Chrome and Android in 2025, especially when the bottleneck has shifted to the ad auction layer and the answer layer.

This reinforces the need for a public options mindset where the government acts as a buyer. Educational institutions, healthcare, and local governments can set procurement terms that ensure openness: any AI assistant serving students or civil servants must allow users to export conversations, publish its model/version watermark, and accept a standard set of content sources (curricula, research, local services) through APIs for others to use. If implemented on a large scale—think state systems and school districts—vendors will adapt. Regulators have spent years debating the theory of harm; buyers can establish a theory of change in contracts right now. Brookings has advocated for a forward-looking policy framework following this ruling; the task is to make that framework practical: interoperability instead of punishment, contracts rather than courtrooms, and speed over spectacle.

Finally, let's talk about measurement. Policymakers often wait for changes in search engine share to indicate progress. However, by the time StatCounter shows a "golden cross," assistants will have won the mindshare that really matters. Instead, we should track the share of discovery that involves assistants—how often information-seeking sessions start with an assistant, how many times the assistant's summary ends the journey, and how many clicks to competing sites follow. Early indications suggest a trend in this direction: ChatGPT is widely available as a search tool, desktop search usage has begun to incline toward Bing, and chatbots are now a measurable source of news. None of this indicates that the incumbent is doomed. It highlights how the monopoly framework used in the 2010s underestimates where power resides in the 2020s: the interface that answers first and best. Our regulations should follow user behavior.

The initial statistic—2.5 billion prompts daily—illustrates why the debate over breakups seems irrelevant now. The court's decision not to split Chrome or Android will neither strengthen nor destroy competition. Competition has shifted to assistants while the case progressed through the courts. Suppose lawmakers aim for a competition that benefits students, teachers, and families. In that case, they need to stop recycling outdated structural solutions and create new avenues, such as licensed data-sharing commons, transparent ad auctions, portable defaults, and procurement that emphasizes openness and verifies it. Antitrust, in its traditional, slow manner, will continue to act as a safety net for egregious behavior. However, the focus should be on creating rules that make it easy to switch and integrate seamlessly. By ensuring the interface is competitive, we won't need to rely solely on link counts to understand if the market is working. If we continue to focus exclusively on breakups, we'll arrive too late, just as the market changes again. Time won't slow down for us; our methods must speed up to keep pace.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Barron's. (2025, September 2). U.S. judge rejects splitting up Google in major antitrust case.

Brookings Institution (Tom Wheeler & Bill Baer). (2025, September). Google decision demonstrates need to overhaul competition policy for AI era.

Competition and Markets Authority (U.K.). (2024, April 11). AI foundation models: Update paper.

European Commission. (n.d.). The Digital Markets Act: Ensuring fair and open digital markets.

Google. (2025, September 2). Our response to the court's decision in the DOJ Search case.

OpenAI. (2024, July 25; updates through February 5, 2025). SearchGPT prototype and Introducing ChatGPT search.

Pew Research Center. (2025, June 25). 34% of U.S. adults have used ChatGPT, about double the share in 2023.

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. (2025, June 17). Digital News Report 2025.

Reuters. (2024, April 10). EU's new tech laws are working; small browsers gain market share.

StatCounter Global Stats. (2025, August). Search engine market share worldwide; Desktop search engine market share worldwide.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2025, September 2). Department of Justice wins significant remedies against Google.

9News/CNN. (2025, September 3). Google will not be forced to sell off Chrome or Android, judge rules in landmark antitrust ruling.