Rethinking AI Energy Demand: Planning for Power in a Bubble-Prone Boom

Rethinking AI Energy Demand: Planning for Power in a Bubble-Prone Boom

Published

Modified

AI energy demand may surge—but isn’t guaranteed Nuclear later; near-term: renewables, storage, shifting Schools should plan for boom or bust with flexible procurement

By 2030, global electricity generation for data centers is expected to exceed 1,000 TWh, about double 2024 levels and nearly 3% of total global electricity generation. This figure is significant. It reflects both the scale of growth in computing and a deeper tension in policy. If we view AI energy demand as fixed and unavoidable, we risk embedding today's hype into tomorrow's power systems. However, this scenario isn't predetermined. Demand will depend on how quickly models are used, business adoption, and profit margins that justify ongoing expansion. If growth slows or if the AI bubble deflates, projections that assume steady increases will be off target. If growth persists, we may struggle to provide enough clean power quickly. Either way, educators, administrators, and policymakers should not rely solely on averages; they must create adaptable strategies to prepare for both increases and decreases.

The United States serves as a stress test. An assessment supported by the U.S. Department of Energy predicts that data centers will grow from approximately 4.4% of U.S. electricity use in 2023 to between 6.7% and 12% by 2028, driven by AI adoption and efficiency gains. BloombergNEF estimates that meeting AI energy demand could require 345 to 815 TWh of power in the U.S. by 2030, translating to a need for 131 to 310 GW of new generation capacity. These estimates vary widely because the future is genuinely uncertain. They depend on factors such as usage rates, inference intensity, cooling technology, and hardware advancements. This uncertainty should inform public investment and campus procurement strategies: plan for peaks while being prepared for plateaus.

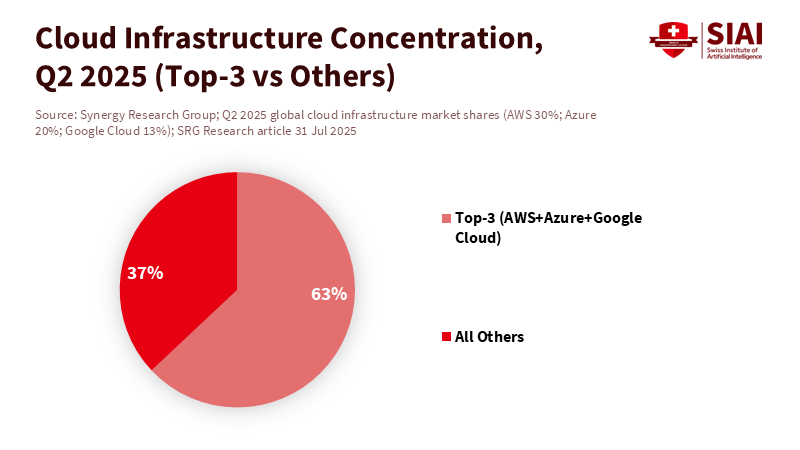

The standard narrative is straightforward: AI chips consume a lot of power, cloud demand is increasing, and grids are under pressure; thus, we must expand clean power, particularly nuclear energy. This chain of reasoning holds some truth but is incomplete. The missing element is the conditional nature of demand. Much of the anticipated load growth relies on business models—such as autonomous systems taking over many white-collar jobs—that haven't yet proven effective at scale. If those assumptions don't hold, the story about AI energy demand shifts from a steep rise to a plateau. Our goal is to create policies for energy and education that apply to both potential outcomes, avoiding the pitfalls of excessive optimism or pessimism.

Productivity Claims vs. Power Reality

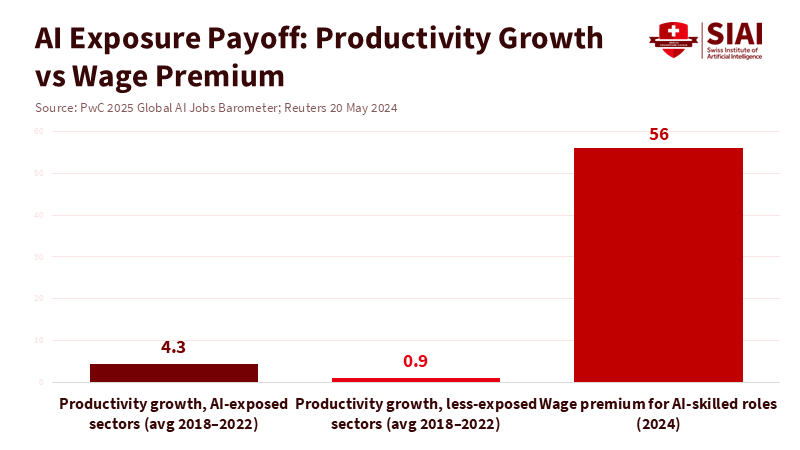

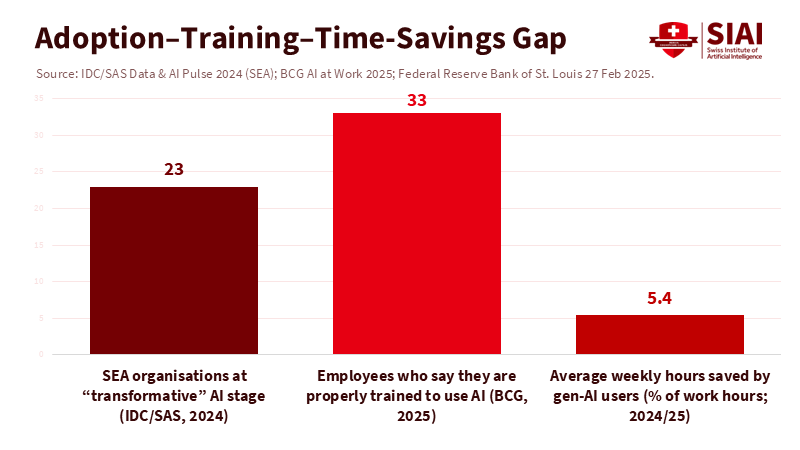

Evidence on productivity in specific situations is encouraging. In a significant field study, providing a generative AI assistant to over 5,000 customer support agents increased the number of issues resolved per hour by about 14% on average, with greater gains for less experienced staff. This indicates real improvements at the task level. However, this alone does not prove that automated systems will replace a large share of jobs or maintain the high inference volumes needed to ensure rapid growth in AI energy demand through 2030. Overall productivity is essential because it funds capital expenditures and keeps servers operational. In 2024, U.S. non-farm business labor productivity grew by about 2.3%. This is good news, but it isn't just about AI, nor is it enough to provide a substantial change to settle the energy debate.

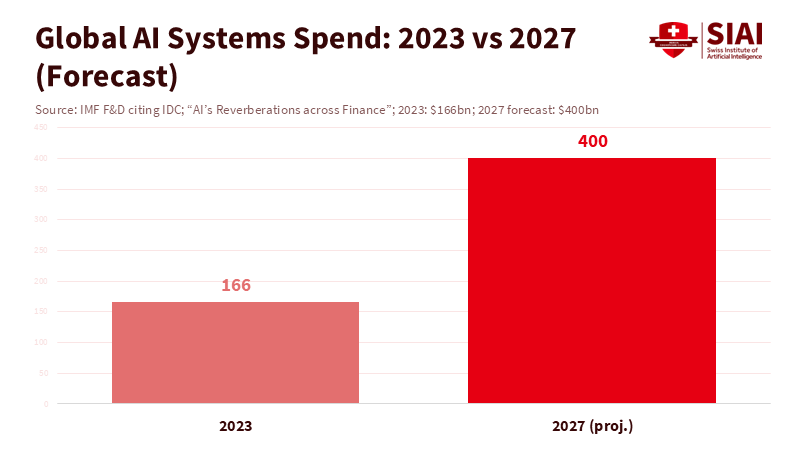

Macroeconomic signals are mixed. Analysts have highlighted a notable gap between the capital expenditures for AI infrastructure and current AI revenues. Derek Thompson and others summarize estimates suggesting spending on AI-related data centers could reach $300 to $400 billion by 2025, compared to much lower current revenues—typical indicators of a speculative boom. Even some industry leaders acknowledge bubble-like traits while emphasizing the necessity for a multi-year runway. If revenue growth falls short, usage will shift from exponential to selective, leading to a decline in AI energy demand. This possibility should be considered in grid and campus planning—not as a prediction, but as a scenario with specific procurement and contracting consequences.

The baseline for data centers is also changing rapidly. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that global electricity consumption by data centers could double to about 945 TWh by 2030, growing roughly 15% per year, which is over four times the growth rate of total electricity demand. U.S. power agencies anticipate a break from a decade of flat demand, driven in part by AI energy needs. However, the IEA also highlights significant differences in the sources of new supply: nearly half of the additional demand through 2030 could be met by renewables, with natural gas and coal covering much of the rest, while nuclear energy's contribution will increase later in the decade and beyond. This mix highlights the policy dilemma: should we aim for slower demand growth, faster clean supply, or both?

Nuclear's Role: Urgent, but Not Instant

Nuclear power has clear advantages for meeting AI energy demand: high capacity factors, stable output, a small land footprint, and life-cycle emissions comparable to those of wind power. In 2024, global nuclear generation reached a record 2,667 TWh, with average capacity factors around 82%. This reliability is valuable to data center operators. These attributes are crucial for long-term planning. The challenge lies in time. Recent data indicate that median construction times range from approximately 5 to 7 years in China and Pakistan, to 8 to over 17 years in parts of Europe and the Gulf, with some western projects taking well beyond a decade. Small modular reactors, often touted as short-term solutions, have faced cancellations and delays; the flagship project in Idaho was terminated in 2023. In other words, while nuclear is a strategic asset, it alone cannot handle the immediate surge in AI energy demand.

This timing issue is significant because the period from 2025 to 2030 is likely to be critical. Even optimistic timelines for small modular reactors suggest that the first commercial units won't be ready until around 2030; many large reactors now under construction will not connect to the grid before the early to mid-2030s. Meanwhile, wind and solar energy sources are being added at unprecedented rates—around 510 GW of new renewable capacity in 2023 alone—but their variable generation and connection backlogs limit how much of the AI surge they can support without storage and transmission improvements. The practical takeaway is a three-part plan: push for nuclear expansion in the 2030s, accelerate renewable energy and storage investments now, and implement demand-side strategies to manage AI energy demand in the meantime.

Even in a nuclear-forward scenario, careful procurement matters. Deals for data centers near campuses should combine long-term power purchase agreements with enforceable clean-energy guarantees, not just claims about the grid mix. Where nuclear is feasible, offtake contracts can support financing; where it is not, long-duration storage and reliable low-carbon options—including geothermal and hydro updates—should form the basis of the energy strategy. The goal of policy is not to choose winners, but to secure reliable, low-carbon megawatt-hours that align with the hourly demands of AI energy.

What Schools and Systems Should Do Now

Education leaders are in a unique position: they are significant electricity consumers, early adopters of AI, and trusted community conveners. They should respond to AI energy demand with three specific actions. First, treat demand as something that can be shaped. Model the load under two scenarios: ongoing AI-driven growth and a moderated rate if automated systems don't deliver. Align procurement with both scenarios—short-term contracts with flexible volumes for the next three years, and longer-term clean power agreements that expand if usage proves sustainable. Include provisions to reduce usage during peak times, and implement price signals that encourage non-essential tasks to be done during off-peak hours. This same approach should apply to campus research groups: establish scheduling and queuing rules that prioritize daytime solar energy whenever possible and enhance heat recovery from servers for buildings.

Second, connect education to energy use. Update curricula to specify AI energy demand within computer science, data science, and EdTech programs. Teach energy-efficient model design, including quantization, distillation, and retrieval, to reduce inference costs. Introduce foundational grid knowledge—such as capacity factors and marginal emissions—so graduates can develop AI that acknowledges physical limits. Pair this learning with real-world procurement projects: allow students to analyze power purchase agreement terms, claims of additionality, and hourly matching. Future administrators will need this knowledge as much as they require skills in privacy or security.

Third, plan for both growth and decline. If usage skyrockets as anticipated, the U.S. could need between 11% and 26% more electricity by 2030 to support AI computing; campuses should prepare to adjust workloads, invest in storage, and strengthen distribution networks. If the bubble bursts, renegotiate the minimum terms of offtake agreements, direct surplus clean energy toward electrifying fleets and buildings, and retire the least efficient computing resources early. Taking these approaches safeguards budgets and supports climate goals. It is crucial to reject the notion that the only solution is to produce more energy. Good policy must also address demand.

Anticipating the Strongest Critiques

One critique suggests that efficiency will outpace demand. New designs and improved power utilization effectiveness (PUE) could limit AI energy needs. This is a plausible argument. However, history warns of the Jevons paradox: lower costs per token can lead to increased consumption. Even the most positive efficiency projections indicate that overall demand will still rise in the IEA's base case, as user growth outweighs savings from improved efficiency. Others argue that AI could offset its energy costs through enhanced productivity. Studies at the task level show gains, particularly among less experienced workers, and U.S. productivity has improved. Yet, these advancements are not substantial enough at this point to guarantee the revenue streams necessary to support permanent, exponential growth. It is wiser to plan for different possible outcomes, rather than deny potential issues.

A second critique argues that nuclear energy can meet the rising demand if we "choose to build." We should indeed make that choice—quickly and safely. However, current timelines present challenges. Recent global construction times vary greatly; early adopters of small modular reactors have faced setbacks, and large projects in the West continue to have extensive delays. While nuclear is necessary in the mix for the 2030s, it is not a quick fix for AI energy demands in 2026. This is why procurement strategies must combine short-term renewable and storage solutions with long-term firm sources. Regulators must also expedite transmission and interconnection processes; without proper infrastructure, new clean energy resources cannot reach new demand.

A third critique argues that fears of an "AI bubble" are exaggerated. This may be true. However, even industry insiders recognize bubble-like characteristics in the market while suggesting that any downturn may still be years away. For public institutions, the appropriate response is not to stake everything on either scenario. Instead, they should ensure flexibility: secure adaptable contracts, staged developments, colocated storage, and systems that maximize value from every kilowatt-hour. This strategy works well in both growth and downturn periods.

Design for Uncertainty, Not For Averages

The key numbers are concerning. Global AI energy demand for data centers could surpass 1,000 TWh by 2030. In the U.S., AI could account for 6.7% to 12% of total electricity by 2028, and meeting growth needs by 2030 could require adding 131 to 310 GW of new capacity. These estimates validate the need for urgent action without leading to despair. They also remind us to stay humble about what the future holds: if automated systems fail to generate substantial productivity consistently, usage will decline, and long-term energy investments based on steady growth will fall short. Conversely, if AI continues to expand, every clean megawatt we can create will be essential, with nuclear energy playing a more significant role later in the decade and into the 2030s. The unifying theme is design. Institutions should approach AI energy demand as a variable they can control—shaped through contracts, software, education, and operations. This involves securing flexible offtake today, investing in robust low-carbon supply tomorrow, and maintaining a constant focus on efficiency. It also means graduating students who understand how to work with the existing grid and the new grid we need to build. The call to action is clear: prepare for growth, protect against downturns, and ensure that every incremental terawatt-hour is cleaner than the last.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BloombergNEF. (2025, October 7). AI is a game changer for power demand.

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. (2023). Generative AI at Work (NBER Working Paper No. 31161).

Ember. (2025, April 8). Global Electricity Review 2025.

IEA. (2024–2025). Energy and AI: Energy demand from AI; Energy supply for AI.

IEA. (2024). Electricity 2024 – Executive Summary.

IEA. (2023). Renewables 2023 – Executive Summary.

LBNL/DOE. (2024, December 20). Increase in U.S. electricity demand from data centers. U.S. DOE summary.

Reuters. (2025, February 11). U.S. power use to reach record highs in 2025 and 2026, EIA says.

U.S. BLS. (2025, February 12). Productivity up 2.3 percent in 2024.

World Nuclear Association. (2024–2025). World Nuclear Performance Report; capacity factors and 2024 generation record.

World Nuclear Industry Status Report. (2024). Construction times 2014–2023 (Table).

Thompson, D. (2025, October 2). This Is How the AI Bubble Will Pop.

The Verge. (2025, Aug.). Sam Altman says "yes," AI is in a bubble.

Business Insider. (2025, Oct.). Former Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger says AI is a bubble that won't pop for several years.