Analyzing the U.S.-China trade conflict using Comparative Advantage Theory and the Cobb-Douglas Production Function

Recently, the U.S.-China conflict has intensified. Beginning with trade restrictions on China under the Trump administration in 2018, the Biden administration, which took office in 2021, has continued to take bold steps aimed at domestic manufacturing recovery and tightening control over China. These efforts include bipartisan legislation such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS and Science Act. As a result, the global industrial landscape is undergoing significant restructuring.

At one time, U.S. manufacturing was unrivaled, but it gradually declined under the pressure of “Triffin’s Dilemma,” a result of the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and increasing global competition. However, a recent wave of U.S.-China “decoupling” has shifted the comparative advantage of capital and labor between the two countries. As a result, U.S. manufacturing is showing signs of revival, with a sharp increase in employment. In contrast, China’s once-explosive manufacturing growth is shrinking due to the aggressive trade sanctions imposed by the U.S. Meanwhile, America’s IT and financial sectors are facing a wave of layoffs, bringing cold news to industry workers.

This column reinterprets the newly evolving industrial structures of the United States and China by applying the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, an international trade theory based on comparative advantage in economics, the Cobb-Douglas production function, a mathematical tool of microeconomics, and regression analysis from statistics.

Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem and Cobb-Douglas Production Function

Before examining the U.S.-China conflict, it is essential to introduce the theoretical tools that will aid in its interpretation. First, the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem is a theory in international economics which states that trade occurs between countries due to differences in their factor endowments and the varying factor intensities required to produce different goods. The theorem builds upon David Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage but introduces a slightly different perspective. While Ricardo’s theory suggests that comparative advantage arises from differences in technological capabilities, the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem asserts that comparative advantage and trade stem from differences in factor intensities, such as labor (L) and capital (K), which are used in the production process. For example, China has an abundance of labor, while the U.S. is rich in capital and technology. As a result, the two countries trade labor-intensive goods for capital-intensive goods.

The Heckscher-Ohlin theorem can be expressed in the form of a Cobb-Douglas production function, which is commonly used in economics. This function illustrates the relationship between factor intensities (L for labor, K for capital) and output (Y) and is widely used to analyze how the inputs of labor and capital contribute to factor productivity in a country or a specific industry. It helps to determine how much productivity is generated when labor and capital are employed in production.

Estimating the “Elasticities” of the Cobb-Douglas Production Function through Regression Analysis

Let’s formulate the Cobb-Douglas production function for a country, where the total output is denoted by $Y_i$, labor input by $L_i$, capital input by $K_i$, and the remainder of the output that cannot be explained by labor and capital (the residual) is represented by $exp(u)$, as follows:

\[

Y = exp(\beta_0) \cdot L^{\beta_L} \cdot K^{\beta_K} \cdot exp(u) \quad \cdots ~(1)

\]

In the Cobb-Douglas production function, “elasticities” or “factor productivities” are represented by $\beta_L$ and $\beta_K$, and these can be easily estimated through a slight transformation of the equation. First, by taking the logarithm of both sides of equation 1, it transforms into equation 2.

\[

\log{Y} = \beta_0 + {\beta_L} \log{L_i} + {\beta_K} \log{K_i} + u \quad \cdots ~(2) \]

Equation 2 takes a familiar form. It is a linear regression equation where $\log{Y}$ is the dependent variable and $\log{L}$ and $\log{K}$ are the independent variables. By taking the partial derivatives of $\log{L}$ and $\log{K}$, we can obtain $\beta_L$ and $\beta_K$. In microeconomics, these regression coefficients are referred to as the “elasticities of substitution” for the factors of production, denoted as $e_{LY}$ and $e_{KY}$.

\begin{align*}

\beta_L &= \cfrac{\partial \log{Y}}{\partial \log{L}} = \cfrac{dY}{Y}*\cfrac{L}{dL} = \cfrac{dY/Y}{dL/L} = e_{LY} \\

\beta_K &= \cfrac{\partial \log{Y}}{\partial \log{K}} = \cfrac{dY}{Y}*\cfrac{K}{dK} = \cfrac{dY/Y}{dK/K} = e_{KY}

\end{align*}

By using OLS (Ordinary Least Squares) estimation in equation 2, we can get $\beta_L$ and $\beta_K$, allowing us to quantitatively analyze how elastically the output of a given country increases when additional labor and capital are input.

Trade Arising from Differences in the Regression Coefficients

In summary, by estimating the $\beta_L$ and $\beta_K$ of the Cobb-Douglas production function, we can quantitatively assess the labor and capital productivity of each country. Based on this Cobb-Douglas production function, the reasons for trade between countries can be explained using the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem.

For example, let’s assume that South Korea is relatively capital-abundant, while Chile is labor-abundant. In this case, smartphones are considered capital-intensive goods, requiring more capital than labor, while wine is labor-intensive, requiring more labor than capital. Thus, in the production of smartphones, $\beta_K$ would be greater than $\beta_L$, whereas in the production of wine, $\beta_L$ would be greater than $\beta_K$. According to the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, due to differences in factor intensities ($\beta_L$, $\beta_K$), South Korea would have a comparative advantage in producing capital-intensive smartphones at a lower cost, while Chile would have a comparative advantage in producing labor-intensive wine at a lower cost, leading to trade.

At this point, we have all the necessary tools for analysis. However, before diving in, let’s first take a look at the recent shifts in the industrial landscape of the U.S. and China due to their ongoing conflict

Increase in U.S. Manufacturing Employment Rate

The U.S. export-based industries, particularly manufacturing, have consistently recorded trade deficits and gradually declined due to the petrodollar system that began in the mid-to-late 1970s. This decline accelerated further during the 1980s under Ronald Reagan’s administration, as the consecutive oil shocks triggered domestic economic recessions, leading to a steep downfall of labor-intensive manufacturing industries. To counter this, the government implemented tax cuts, public spending, and massive defense expenditures to curb the recession dramatically. Subsequently, the U.S. experienced nearly 40 years of low interest rates and low inflation, and until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the manufacturing employment rate had been steadily recovering.

However, in the wave of the COVID-19, the economy contracted once again, leading to the overnight shutdown of major automobile assembly plants and dealerships. Automobile manufacturing came to a sudden halt, and in the food industry, numerous reports emerged of workers contracting and dying from the virus, prompting factories to shut down and causing a massive loss of jobs. In response, the U.S. government implemented a large-scale quantitative easing of $4.5 trillion, which helped boost employment rates, and the manufacturing sector began to recover.

Amidst these developments, the U.S., under the leadership of President Biden, aggressively pushed forward the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the CHIPS and Science Act. These initiatives aimed to strengthen the domestic economy by overhauling bridges, roads, and rural areas across the country. As a result, not only did the U.S. curb the growth of China’s semiconductor industry, a key sector of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, but it is also now moving to reshape the global semiconductor landscape with the U.S. at its center.

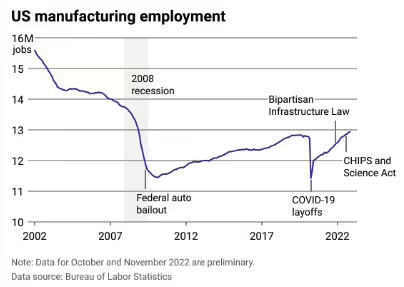

Buoyed by this political momentum, the manufacturing sector has continued its upward trend. According to the Financial Times, as of June, U.S. manufacturing employment has increased by nearly 800,000 since President Biden took office, with around 13 million people now employed in the sector, the highest level since the 2008 global financial crisis. As shown in Figure 1, employment rates rose sharply during key periods such as the pandemic-era quantitative easing and the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and CHIPS and Science Act.

The Grim U.S. Financial and Tech Sectors

In stark contrast to the manufacturing sector, which is gearing up for significant growth, major U.S. tech companies have been undergoing large-scale layoffs since the latter half of last year. Leading the wave of employment cuts are global IT giants such as Amazon and Meta, with many other U.S. tech firms following suit. According to Layoffs.fyi, a site that tracks layoffs in the U.S. tech industry, 1,058 IT companies laid off a total of 164,709 employees last year alone. Notably, in November, Amazon laid off 10,000 employees, while Meta cut 11,000 jobs.

The layoffs at major tech companies have continued into this year. Following last year’s cuts, Amazon has laid off an additional 17,000 employees so far in 2023. While Apple announced plans to reduce its operating budget to avoid restructuring, some reports suggest that the company began cutting staff in April, starting with its retail team at the U.S. headquarters in California.

Meanwhile, the U.S. financial sector has not been spared from the wave of layoffs. In May, CNBC reported that major Wall Street investment banks such as Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, and Citigroup carried out significant job cuts. Morgan Stanley laid off around 3,000 employees by the end of June, amounting to 5% of its total workforce based in New York. Additionally, Citigroup and Bank of America also announced the dismissal of hundreds of employees in May, bringing grim news to the financial industry.

Declining China’s Manufacturing Sector Amid U.S.-China

China, which is in direct hegemonic competition with the U.S., is experiencing significant losses in its manufacturing sector. This is due to the intensifying “decoupling” between the two countries, driven by the Biden administration’s domestic-focused initiatives such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act, which aim to strengthen U.S. technological sanctions on China. Additionally, ongoing tariff disputes between the two nations have further escalated the situation.

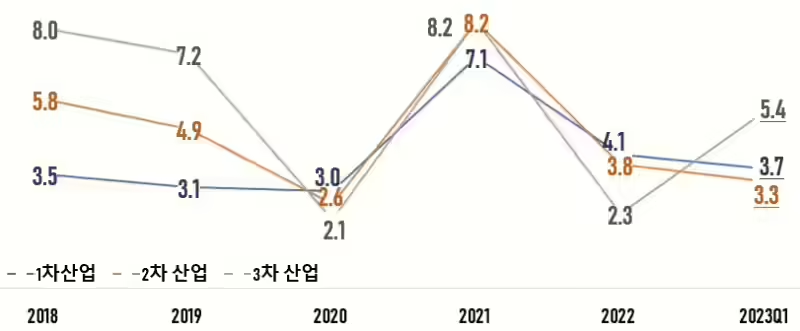

China’s manufacturing growth has significantly slowed due to geopolitical tensions with the U.S. As shown in Figure 2, China’s secondary industry (related to manufacturing) began to decline starting in 2021, when the U.S. started implementing parts of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law as part of its efforts to strengthen domestic competitiveness and achieve self-sufficiency.

In the same context, data released by China’s General Administration of Customs on July 13 showed that China’s export value in June was $285.3 billion, a 12.4% decrease compared to the same month last year. This figure falls short of both the previous month’s -7.5% and the market expectation of -9.5%.

An Explanation of the U.S.-China Conflict Based on the Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem

Through the discussion so far, we can see that between 2021 and 2022, when national efforts toward “self-sufficiency” and “decoupling” between the U.S. and China began to intensify, the two countries started to take divergent paths in manufacturing. Additionally, we’ve observed that U.S. sectors such as Wall Street and Big Tech are facing a wave of layoffs, leading to a general downturn in the financial and IT industries.

Here, we can raise a few questions. Why have the industrial structures of the U.S. and China evolved in opposite directions? For instance, why have the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act, aimed at reducing U.S. dependence on China, revitalized U.S. manufacturing while leading to the decline of China’s manufacturing sector? Could U.S. and Chinese manufacturing not have risen together when the U.S. decided to focus on strengthening its domestic market? And why, seemingly unrelated, has the U.S. financial and IT sectors faced a downturn?

Let’s view the U.S.-China conflict and industrial structural changes through the lens of the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem. From 1970 to 2022, the U.S. experienced a decline in its export competitiveness in manufacturing due to the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and instead focused on capital-intensive industries like finance and IT. It’s also important to acknowledge that the flow of global capital into the U.S. as a reserve currency issuer played a significant role in this shift. During this period, the U.S. had a comparative advantage in “technology” or “capital,” whereas China, by leveraging its cheap labor, focused on labor-intensive industries based on primary sectors, giving it a comparative advantage in “labor.” By concentrating on what they did best, the U.S. and China grew their economies by trading technology-intensive goods and labor-intensive goods with one another.

However, with the recent passage of laws such as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the CHIPS and Science Act, the U.S.-China technological competition has intensified, leading to a resurgence in U.S. manufacturing. Additionally, as labor costs have declined in the U.S., the comparative advantage between the U.S. and China has started to shift. With the relative price of labor compared to capital decreasing in the U.S., resources have gradually been reallocated toward manufacturing. As a result, capital-intensive industries like finance and IT have seen a reduction in labor input. In contrast, China’s labor-intensive manufacturing sector has been shrinking due to aggressive U.S. sanctions, causing the relative price of labor to rise compared to capital.

Changes in the U.S.-China Industrial Structure Due to Differences in the Regression Coefficients

Let’s revisit the U.S.-China conflict through the lens of factor productivity (elasticity) in the Cobb-Douglas production function. The total output of a country is denoted by $Y_i$, labor input by $L_i$, capital input by $K_i$, and the remainder of the output that cannot be explained by labor and capital (the residual) by $exp(u)$. The Cobb-Douglas function can be expressed as follows. In this case, let’s assume there are only two countries, where $i$ represents either the U.S. ($U$) or China ($C$).

\[

Y = exp(\beta_0) \cdot L^{\beta_L} \cdot K^{\beta_K} \cdot exp(u)

\]

Before the implementation of the petrodollar system and the resulting large trade deficits, the U.S. in the pre-1980s likely had higher values for both $\beta_L^U$ (labor elasticity) and $\beta_K^U$ (capital elasticity) compared to China. The reason is that the U.S., with its robust manufacturing sector focused on secondary industries, would have had higher labor productivity than China, which was still primarily focused on the primary sector (light industries) during its early stages of economic growth. Additionally, the U.S. had significantly increased productivity through capital investments in mechanization and automation, suggesting that its capital productivity was also higher than that of China, which at the time relied more on manual labor.

On the other hand, from the 1980s until just before the COVID-19 outbreak, the U.S. saw its manufacturing sector decline under the petrodollar system, while China experienced explosive growth due to continuous market reforms and its entry into the WTO. As a result, in the manufacturing sector, both $\beta_L^U$ (labor elasticity) and $\beta_K^U$ (capital elasticity) in the U.S. likely became lower than those of China during this period.

However, between 2021 and 2022, as the U.S. took aggressive measures to counter China, its manufacturing sector began to revive. As a result, in manufacturing, the U.S.’s $\beta_L^U$ (labor elasticity) and $\beta_K^U$ (capital elasticity) are now catching up with those of China.

Applying the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, it appears that due to the recent U.S.-China conflict, the U.S. has not only gained an absolute advantage in both $\beta_L^U$ (labor elasticity) and $\beta_K^U$ (capital elasticity) over China, but there are also signs that $\beta_L^U$ may be surpassing $\beta_K^U$. This indicates that labor is shifting toward the manufacturing sector in the U.S., while in China, trade sanctions are causing $\beta_L^C$ (labor elasticity) to decline, making $\beta_K^C$ (capital elasticity) relatively larger.